Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes, Knees and Toes...

Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes, Knees and Toes...

- Home

- POMA

- POMA Foundation

- DO Voices

- Residents & Students

- Education

- Advocacy

- Affiliates

- Public

Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes, Knees and Toes...

Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes, Knees and Toes...

I have to admit, when I was young, I did not like to color. We all had to do it in elementary school. Coloring was a skill that taught us how to follow instructions, express creativity and stay in the lines. As a child, I followed instructions well, was more creative with words rather than drawing, and honestly, I had trouble staying in the lines, (though, my difficulty staying in the lines helped discover a vision problem).

I have to admit, when I was young, I did not like to color. We all had to do it in elementary school. Coloring was a skill that taught us how to follow instructions, express creativity and stay in the lines. As a child, I followed instructions well, was more creative with words rather than drawing, and honestly, I had trouble staying in the lines, (though, my difficulty staying in the lines helped discover a vision problem).

How are you doing? This is usually the first question I ask my patients when I see them in the office. I suspect like many of you, the typical answers I get now (terrified, I don’t know, bad) are different than what I would have gotten six months ago (good, ok, not bad). What hasn’t changed is the thing that patients most need from us – information.

How are you doing? This is usually the first question I ask my patients when I see them in the office. I suspect like many of you, the typical answers I get now (terrified, I don’t know, bad) are different than what I would have gotten six months ago (good, ok, not bad). What hasn’t changed is the thing that patients most need from us – information.

Postdoctoral training is rigorous and time-consuming. The emotional and physical implications of residency and fellowship call for trainees to take what little time they do have to participate in enjoyable activities that keep them going. As co-residents at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, we found the popular indoor cycling class, SoulCycle, to be our go-to wellness activity. Since our intern year, we have been arranging meet-ups at the music-blaring, sweat-dripping, lights-flashing dark room that is SoulCycle. Now, carrying on into our separate fellowships, we still find time to enjoy a 45-minute jam and cycle “sesh.”

Postdoctoral training is rigorous and time-consuming. The emotional and physical implications of residency and fellowship call for trainees to take what little time they do have to participate in enjoyable activities that keep them going. As co-residents at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, we found the popular indoor cycling class, SoulCycle, to be our go-to wellness activity. Since our intern year, we have been arranging meet-ups at the music-blaring, sweat-dripping, lights-flashing dark room that is SoulCycle. Now, carrying on into our separate fellowships, we still find time to enjoy a 45-minute jam and cycle “sesh.”

I’m fortunate to sit on our residency leadership committee at Lehigh Valley Health Network and attend conferences where we discuss a wide range of physician leadership topics. A common topic is physician burnout and what healthcare leaders can do to mitigate it. At a recent meeting, we discussed an article from the Mayo Clinic Proceedings titled “Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout.” The authors, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD and John H. Noseworthy, MD, cite evidence suggesting that physicians who spend just 20% of their professional activities focused on the work they find most meaningful are at a dramatically lower risk for burnout. There was also a ceiling effect to this benefit at 20%, meaning that physicians who spend 50% of their time in the area most meaningful to them had no further decrease in burnout rate.

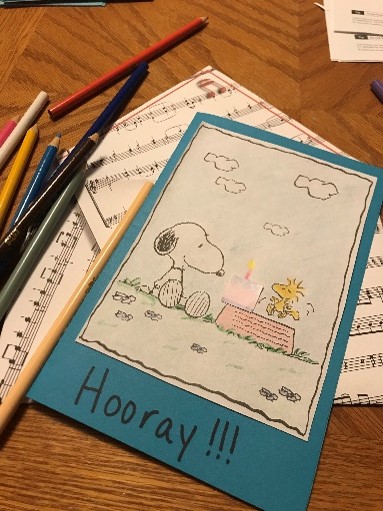

“Art is the queen of all sciences communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world.” If this statement hadn’t already been so eloquently articulated by Leonardo Da Vinci, it would have been my own. These words perfectly illustrate my view of the relationship between art and science, and how this relationship has fueled my unique path towards a career in medicine.

“Art is the queen of all sciences communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world.” If this statement hadn’t already been so eloquently articulated by Leonardo Da Vinci, it would have been my own. These words perfectly illustrate my view of the relationship between art and science, and how this relationship has fueled my unique path towards a career in medicine.

It doesn’t matter if you are new to medicine or more experienced, we will all be faced with a situation where a patient we are caring for dies. Regaining your strength when this occurs is a challenge. Depending on the situation there may be sadness, inadequacy, fear and loss of self-confidence. Allowing yourself to feel these emotions and move on is critical.

I seldom park in the designated “Physician Parking” spaces. Mostly, because during this time of very active construction at the hospital where I work (or as I refer to it, the “employee wellness program” encouraging all of us to get that 10,000 plus steps in a day) I have found a strategically placed, out of the way “spot” that no one else appears to have claimed. It is not designated for patients, it is not a handicapped spot, I have to travel a couple of side streets to get to it, but it works for me.

As residents, working 12 hours a day, we often wonder, “How do we do it all?”. It feels easy to be overwhelmed at the idea of achieving wellness. While we strive to have the perfect professional and personal life balance, it sometimes feels impossible to read, exercise, do household chores, and fulfill the role of a loving partner/parent/child/friend when we return back home.

As residents, working 12 hours a day, we often wonder, “How do we do it all?”. It feels easy to be overwhelmed at the idea of achieving wellness. While we strive to have the perfect professional and personal life balance, it sometimes feels impossible to read, exercise, do household chores, and fulfill the role of a loving partner/parent/child/friend when we return back home.

I knew residency wouldn’t be easy for someone as beholden to REM cycles as I am, though I naively believed I could make it through four years of training unaffected by their relative absence. It turns out that was wishful thinking. Although I took an oath to do no harm to my patients, learning how to practice medicine came at the cost of my own health and well-being.

I knew residency wouldn’t be easy for someone as beholden to REM cycles as I am, though I naively believed I could make it through four years of training unaffected by their relative absence. It turns out that was wishful thinking. Although I took an oath to do no harm to my patients, learning how to practice medicine came at the cost of my own health and well-being.

Resident wellness is an important part of today's medical training. We at the Washington Hospital Family Medicine Residency have had the good fortune of having support from our administration in maintaining wellness of the residents in our program. With the help of the POMA Mental Health Task Force and the POMA foundation, we were granted funding to support our idea to create an event combining resident wellness with nutrition integrated with medicine, notably, culinary medicine, inspired by the Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine at Tulane University.

On my first day in the hospital as a new intern, I had the healthy amount of fear that most new DOs have. I anticipated that long hours and dedication to taking every opportunity to learn would leave very little time to spend with family, friends or for self-care. I thought I would be putting my personal life on pause during the next three years in order to focus on becoming the best clinician I could become. Starting a new hobby or interest didn’t even cross my mind. As a single person entering the rigorous life of residency, I also thought dating would be off the table for the foreseeable future.

On my first day in the hospital as a new intern, I had the healthy amount of fear that most new DOs have. I anticipated that long hours and dedication to taking every opportunity to learn would leave very little time to spend with family, friends or for self-care. I thought I would be putting my personal life on pause during the next three years in order to focus on becoming the best clinician I could become. Starting a new hobby or interest didn’t even cross my mind. As a single person entering the rigorous life of residency, I also thought dating would be off the table for the foreseeable future.